The term commissioning comes from shipbuilding. This quote, from the California Commissioning Collaborative, expands on that definition: “A commissioned ship is one deemed ready for service. Before being awarded this title, however, a ship must pass several milestones. Equipment is installed and tested, problems are identified and corrected, and the prospective crew is extensively trained. A commissioned ship is one whose materials, systems, and staff have successfully completed a thorough quality assurance process.”

Similar to how ships are commissioned before setting sail for the first time, owners often elect to have their buildings commissioned before being turned over to operations. This process ensures a facility’s systems operate as they should, and the building is set to perform at peak efficiency. A building can be commissioned as part of the construction process or after operations, which is also known as existing building commissioning (EBCx). This article will discuss the different types of existing building commissioning, the advantages and disadvantages of each, and why owners should invest in MBCx/CC, even if their buildings were initially commissioned.

First, it’s important to understand the definitions associated with commissioning and existing building commissioning.

Commissioning

New construction commissioning, or simply commissioning (Cx), occurs on new construction projects and should be performed by experienced commissioning authorities/agents (CxA). Commissioning generally occurs in the following order: design, construction, and operations. Commissioning activities start early in the project planning stages and are maintained throughout the design, construction, and final acceptance of the project at a minimum. The commissioning team’s primary goal is to authenticate proper equipment installations, systems operations, and performance according to the project basis of design (BOD) and owner’s project requirements (OPR). The commissioning process provides confirmation, identifies system issues and discrepancies, ensures quality assurance, and verifies if the building is designed and constructed properly, ultimately optimizing the HVAC system’s energy efficiency, system controls, operation performance, and occupancy comfort level as well as increasing the equipment’s useful life and durability. The last step is training, which ensures building staff are prepared to operate and maintain a building’s systems and equipment.

Retro-Commissioning

Most facilities are designed to operate at a certain level of performance. Over time, a facility’s performance may diminish due to age, improper maintenance, or worn-out equipment. Retro-commissioning (RCx) applies the commissioning process to an existing facility that was not previously commissioned. It provides an owner with a means to improve performance of existing buildings by finding ways to optimize systems and replace equipment with new units that are more energy efficient.

RCx generally occurs in the following order: planning, investigation, implementation, and certification. RCx is a combination of efforts of analyzing buildings current energy usage, performance, issues, and implementing energy conservation measures to reduce operation and maintenance (O&M) costs while improving the functionality of the building's systems.

Equipment ideal performance and control sequences of operation degrade over time, resulting in system inefficiency, higher O&M costs, and occupancy discomfort. Depending on the age of the building, RCx can often fix these issues created during design or construction and address problems that have developed throughout a building's life.

Monitoring-Based Commissioning

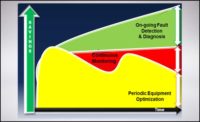

The process of ongoing commissioning along with the implementation of energy savings strategies in an already commissioned site is called monitoring-based commissioning (MBCx). MBCx uses analytical software to track down critical components of equipment at each facility. This analytical software provides the ability to run different diagnostic tests to point out and detect malfunction equipment and observe the overall energy consumption and performance in the building. To put it in a nutshell, MBCx is a clear, comprehensive, data-based approach to verify that building systems operate according to the design documentation. It consists of building management systems (BMS) analysis, energy meter data analysis, and ongoing commissioning support.

Continuous Commissioning

Similar to monitoring-based commissioning, continuous commissioning® (CCx) is an ongoing process designed to resolve operating problems, improve comfort, and optimize energy use for existing facilities. This is often accomplished through building monitoring systems and/or sensors to capture operational data. CCx combines several sustainable strategies that are used in series to examine and perpetually address elements of existing buildings that can be optimized without the need for heavy capital investment.

Continuous commissioning, CC®, and PCC® are registered trademarks of the Texas A&M Engineering Experiment Station, a member of the Texas A&M University System, an agency of the state of Texas. The Energy Systems Laboratory not only implements continuous commissioning but licenses its CC technology and practices to firms. These firms have access to the tools, research, and expertise that make the CC process effective. This select group of engineers and building professionals has the necessary skills and training to quickly identify the best improvement opportunities — those that can be implemented with the least cost while producing the greatest impact.

FIGURE 1: The rotational basis that makes up monitoring-based commissioning (MBCx). Images courtesy of Smith Seckman Reid

MBCx Steps

Setting up a comprehensive MBCx process is fairly straightforward. Before any action is taken, the consultant should create a plan of action and discuss this with building owners and associated contractors. This communication makes sure everyone fully understands what is happening around them and they are onboard with the process.

- Monitor: Working with the building owner or operator, the MBCx agent needs to have access to energy usage and settings for different HVAC equipment in the building. This can often be accomplished by being granted access to past utility bills. The data is gathered, sorted, assigned, and analyzed.

- Once the connection is set up, data can be viewed with an automatic fault detection and diagnostics (AFDD) program. AFDD systems run based on rules designed for each specific site. At this phase, these rules need to be created, modified, and finally run/executed.

- Identify: Issues discovered during AFDD are explained in detail and accompanied by graphs and possible resolutions. The issues are sorted by priority level so the building owner can focus on the most important ones.

- Repair/Fix: The MBCx agent works with facility owners, operators, and other parties to fix the issues in the AFDD report based on the budget, priority level, staff timeline, etc.

- Verify: After the repair is completed, the issue should drop off the next AFDD reports as they are generated periodically. AFDD users will be able to verify the fix and close/sleep the issue so the next report won't include repeated data.

Identifying Issues Via AFDD

Fault detection simply means identifying the issues in any system. It monitors the components of the HVAC system in real time and analyzes the data to notify potential faults and abnormalities in the system. Issues such as temperature not meeting the set point, low delta T in chilled water supply and return, and leaky chilled water valves are caught. Diagnostics refers to investigating the issues and finding out the reasons behind them. It focuses on automatic logic to process points data to pin down possible causes. Diagnostics often come with isolating the system to see how the unit responds to different inputs. For example, if the air-handling unit’s (AHU’s) supply air temperature set point needs to be tested, the operator might need to manually change the OA dbT to the lower and higher limits to see how the system responds to those changes. By automating the FDD process, the software makes the building owner aware of any potential issues and opportunities to save less energy all automatically. Think of AFDD as a consulting firm checking on your system 24/7 without getting reimbursed for labor cost. AFDD enhances the operational performance, improves the overall HVAC system’s energy efficiency, and reduces operational costs significantly.

Keep in mind that:

- AFDD points out the issues and faulty systems, but it is still up to the building owner to fix issues on a timely basis.

- After fixing any issues on-site by a technician, they need to be confirmed by an AFDD user that the issue is fixed. The AFDD user will run the rules next round, and, if the issue is fixed, the user will close/sleep the issue.

- An AFDD report includes a list of issues with highest to lowest priorities based on the impact each individual issue has on the system. Building owners can decide between a list of issues to focus on the ones with the highest priority. Priorities can be given based on the current weather season, budget, staff availability, etc.

FIGURE 2: An automatic fault detection and diagnostics (AFDD) report includes a list of issues with highest to lowest priorities based on the impact each individual issue has on the system.

FIGURE 2: An automatic fault detection and diagnostics (AFDD) report includes a list of issues with highest to lowest priorities based on the impact each individual issue has on the system.

The Pros and Cons to MBCx

Like every project, there are advantages and disadvantages. Below is a short summary of the pros and cons to implementing MBCx.

Pros

Cost: Approving the cost for retro-commissioning needs to be justified and receive higher level approvals, which takes time. MBCx is an ongoing process in which an owner can see the results as he or she spends money. Thus, approving the budget for MBCx is usually a smoother process. Since the cost is less than an RCx project, it doesn’t require upper level management to get involved, which would add to the length of the approval process.

Systems change over time: RCx projects are typically done when there is budget and enough motivation between operation team members. In commercial buildings, RCx is performed every five to six years. If the usage pattern changes or new equipment is added in those five to six years, the adjustments made and settings in place after the RCx efforts would be useless or less effective, and new adjustment will be needed. MBCx notices and alerts building operators to changes immediately. This includes sensor failures, changes in schedule, adding a new pump or chiller, room usage changes, etc.

Sensitivity and measure adjustments: Building occupants are usually very sensitive to temperature changes, which is why facility staff receive tons of hot and cold calls on a regular basis. This creates several problems for the operations team and takes excessive resources. Usually, when there is a hot and cold call, facility staff underwrite the existing settings and control programming and forget to release the point once the issue is resolved. When the system is far apart from the design sequence of operation, the system becomes less efficient and more defective, and it shortens the useful life of equipment. During the AFDD report of MBCx, various formulas are used to bring out abnormalities and excessive usages. An MBCx team will point out the issues and possible resolutions for each individual issue in their report. Facility staff will have the opportunity to remove underwritten programming controls and set points and adjust and smoothen the operation of equipment in the building.

Data collection: The process of trend data collection in RCx projects can be very time-consuming and needs a lot of coordination. If International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP) option A or B is chosen for measurement and verification (M&V), the data needs to be pulled in every phase. In MBCx projects, once the setup is done and systems communicate with each other, no man hours are needed to upload the data in the analytical software.

Lower staffing needs: Since MBCx identifies issues and abnormalities on a regular basis, there is less demand for facility staff to control individual systems. This also minimizes discomfort for occupants as a result of systems working more efficiently with each other and in the most optimized mode.

Cons

Sampling: The bigger the building is, the larger the HVAC system is, hence more equipment is needed to run the HVAC system, and each equipment has its own set of sensors it needs to communicate with. For a typical 500,000-square-foot facility, more than 8,000 endpoints are being utilized and monitored. As an example, the following points need to be controlled in a typical AHU: chilled water valve, hot water valve, temperature sensor, relative humidity sensor, dampers positions, static pressure sensors, VFD speed percentage, etc. Bringing all these points to the analytical software, monitoring them, and running fault detection for them requires a lot of man-hours and might not be cost-effective for a one-time analysis.

Data transfer: At each facility, there is a certain personnel/team that is fully familiar with the building automation system (BAS) system and is authorized to make changes to the system. One of the most important steps in collecting trend data in the analytical software is setting up trend data, collecting, and setting up schedules to send the data to the software. The MBCx team needs to work with the facility staff/BAS control team/BAS company and IT team to receive data regularly. This can prove difficult because working with every one’s schedule and priorities can be challenging and time-consuming.

Data analysis: A large amount of data points is transmitted and collected in the analytical software. This data needs a great amount of attention to sort and remove outliers or bad data. The amount of information from the BAS, its controlling devices, and the subsystem components can be staggering with a massive number of control points to consider.

Lack of data: Trend data collection and transmission can be very frustrating. MBCx works with a large amount of data. Ensuring all points are trended and broadcasted to the analytical software correctly can be challenging. Also, points need to be reviewed on a regular basis to make sure the critical data points are not missed, and they are transmitted to the software.

Software cost: Analytical software is usually costly and comes with a monthly subscription. There is usually a training course that needs to be taken so that users can familiarize themselves with the software's features. Depending on the facility size, study depth, equipment age, type of equipment, and the complexity of the HVAC systems in the facility, the cost, on average, could range from $0.09 per square foot to $0.50 per square foot for the first year of the MBCx study. After the first year, the cost decreases slightly to a range of $0.08 per square foot to $0.15 per square foot for each year going forward (software included).

Rule configuration: Each building has a unique set of HVAC equipment, controls, configuration, and data, which is different from any other building. For MBCx to generate monthly reports, many rules need to be run by software and analyze the data. These rules, which follow a set of diagnostic algorithms, need to be continuously tested and optimized. Improving these algorithms starts from building a model as close as possible to the building’s various systems and modifying them based on existing controls drawings and original/design control drawings. Every building is unique, and a typical set of rules and configurations can’t be applied to every building, usage, weather climate, and type.

Summary

As analytical software technology advances, building energy usage, tracking, and monitoring becomes more common. Often, facility teams don’t have enough resources to deal with the massive amount of data provided by the BAS. This data can be used to improve HVAC energy performance, fix issues, save energy, and increase equipment useful life, but, due to lack of knowledge, time, and insight, nobody takes advantage of this useful data. Data needs to be sorted, organized, categorized, processed, and analyzed before it can lead to any corrective action. MBCx software is built to deal with large amounts of HVAC component data on a regular basis and can analyze and visualize the data.

In addition, MBCx software can dig deeper to identify energy savings measures while being significantly more cost-effective than hand calculations. MBCx has been found to achieve a median cost savings of $0.19 per square foot and 7% annually, and these numbers grow as time passes.

AFDD is a tool that is supported by MBCx software and is a set of rules tailored for each specific facility. These rules are run periodically to generate MBCx-AFDD reports. Each report lists issues with all the details and potential resolutions prioritized based on a client's budget, cost-effectiveness, affected components, etc. Building owners can go through the report and decide on the issues they plan to fix during each AFDD period. Issues will remain open or put to sleep based on whether they have been resolved and can be discovered in the next AFDD report. No matter how good the MBCx team does its job and how complete the AFDD report is, they all can be worthless if they don't lead to insights and corrective actions after the reports are turned in. For MBCx to be successful, owners should cooperate with the MBCx team and fix issues as they arise. Although there are issues with MBCx efforts, an experienced and professional team of consulting engineers should be able to overcome issues such as time, data transfer, data analysis, etc.